Why the Battle of Grahamstown Matters Today

Written by: Dr Rodney Warwick

Over the past two years I have explored the Eastern Cape including Makhanda, formerly Grahamstown. There was little evidence of this landmark change after two centuries, but there soon will be: the road signs, businesses, educational institutions letter-heads will reflect as such. The rather low-profile announcement by Arts and Culture Minister Nathi Mthethwa seven months ago encountered virtual media silence regarding either acclamation or objection. An internet search ironically turned up only one strong comment of dissent, from Steve Hofmeyr - Afrikaans identity/language activist and troubadour.

Ironic because Grahamstown once held a special place in Anglo-South African historical identity; now dustily resplendent with its virtually ignored or vandalised British Settler History. A phenomenon perhaps also connected to a seemingly amorphous local Anglo culture, perhaps deceptively so, critically examined by a number of past historians and writers, amongst whom count: Alan Paton, Guy Butler, Dennis Worrell, John Lambert…one strident voice was John Bond, whose 1956 book, They were South Africans wrote of Grahamstown being the “Mother City of English-speaking South Africa (ESSA)”. Bond penned his aggressive defence of white ESSAs history just after they and their Bloedsappe Afrikaner allies had been swept from political power in 1948 by Afrikaner nationalism then triumphantly mobilised, asserting its symbolic identity and bound for the 1961 Republic.

Mthethwa’s statement preceded the 200th anniversary of 22 April 1819 Battle of Grahamstown; unlike Isandlwana sixty years later - a sole but convincing British defeat by the Zulus - the 1819 engagement draws no affirmation within contemporary historical/political dialogue; not least those whose convictions align with the decolonisation assumptions. As a British/Settler victory “decolonists” would excoriate 1819 as representing another blow in the Eastern Cape historical conquest process, directly connected to core contested issues concerning alleged "stealing" of land. Back in 1981 when I completed my first year BA courses at Rhodes University in History, Politics and Sociology; I do not ever recall any student of lecturer referring to 1819 – not amongst the “fashionably-left” “journ” students; or any other “lefty” radicals; nor amongst the then numerous conservative students - no least the “Rhodies” - resident at Kimberly Hall; the Battle of Grahamstown was unknown and unspoken about.

The memorialization of 1819 erected during the late nineteenth century in High Street, encapsulates part of the Settler historical mythology which grew out of the battle; a story disputed but never emphatically proved fraudulent: French women Elizabeth Salt’s purported valour; during a critical battle point she was claimed to have carried a keg of gunpowder from the village to the besieged barracks a mile away. Relying upon the purported Xhosa custom of sparing women and children during warfare; the memorial now vandalised with red paint depicts Salt, fearless and aloof, gliding past the awestruck almost worshipful Xhosa. It is not clear whether the monument’s intention was also to indirectly compliment Xhosa culture or depict their superstitions as primitive and foolish and behaviour as child-like.

While the paucity of public opposition to the name change amongst settler descendants might relate to a white Anglo South African lack of any deeply felt collective historical identity; the present political climate of instant racial smearing also promotes little inducement towards any opposition regarding public “African assertions”. Or as the first Anglican Dean of Makhanda, Andrew Hunter of the city’s Cathedral recently related to me; the change is rooted in African (Xhosa?) identity issues, besides positive motives such as healing and reconciliation; unintendedly the very arguments advanced by Mthethwa. A John Graham memorial remains within the Cathedral but does not directly extol the 1819 victory.

But academic historical study insists upon analysis based, evidence driven, explanations of events: Historian Hermann Giliomee expounds upon some roots regarding the Dutch colonist/British Settler/Xhosa clashes dating from the late 18th century; most particularly within the Zuurveld between the Sundays and Fish Rivers. All had livestock farming in common, seeking the winter soetveld within the numerous river valleys. And as larger population concentrations manifested, so seasonal stock rotations increasingly resulted in territorial disputes within different Xhosa chiefdoms, as between whites and blacks.

Racial misunderstandings, Giliomee continues, had further likely genesis in Xhosa assumptions that their being an open society, to a greater or lesser degree; the numerically much smaller colonists would in time integrate into Xhosa society through intermarriage and other interactions; as had long occurred between Xhosa with some Khoi groupings. But if true, the possibility of inter-marriage and syncretism of European and Xhosa cultures was a crass assumption for the Xhosa to make. Barring a few individuals, colonist Christian and European cultural and material norms of the period ensured such could never happen; exceptions including whites either stranded without recourse – sailors wrecked in previous centuries along the Transkei coast - or desperados fleeing colonial justice.

1819, like the Nine Frontier Wars from 1779 to 1878 possessed a complex intra-racial tapestry; British troops and Afrikaner burgers almost always sided with one another; but significant regular antipathies between burgers and British colonial governance existed, leading to occasional brush-fire insurrections. The Xhosa groupings were markedly fissured by multiple alliances and motives, but most particularly via competing chiefdoms. During the 1819 battle at the British barracks site near today’s Fort England hospital, it was purportedly Khoi hunters and Khoi/Colored recruits of the Cape Regiment, fighting alongside British troops, who delivered the fatal blow to the Xhosa.

The historical mythology surrounding Makhanda or Nxele relates to him considered by the Xhosa as capable of divining events; he had prior contact with whites and was particularly impressed by missionary Dr Vanderkemp, a champion of the Khoi and to a lesser extent, the Xhosa. Makhanda’s attention was caught by Christian teachings regarding the Resurrection of the Dead. The Xhosa of the period acknowledged a Supreme Being, but even those influenced by the missionaries hardly necessarily embraced or comprehended central Christian teachings. It was Makhanda who apparently initially influenced the Xhosa to bury their dead, rather than abandon the dying or the dying in secluded places. Like Nongqawusa 37 years later, Makhanda communicated prophecies of Xhosa dead arising and whites being swept away.

The leadership paramountcy disputes amongst the Xhosa had long baffled British colonial leadership determined to enforce an end regarding the perennial cattle-raiding and retributions from both sides. No less so than on 2 April 1817 when at the Kat River near Fort Beaufort today. Governor Somerset met the prominent chief Gaika accompanied by his rival Ndlambe, with both Xhosa men being reluctant to so confer. Gaika protested his incapacity to curb the cattle stealing by chiefdoms over which he had neither power nor obligation to control. But Somerset insisted he would negotiate with no other chief.

Either the pressure to desist from being duplicitous; or exasperated and defeated by Somerset’s attitude, or actually confident of asserting his authority, Gaika promised to suppress cattle raids and very severely punish offenders. Within this fractious situation open to much historical speculation, Makhanda who was also present gave his loyalty to Ndlambe, then further influencing other disputing chiefdoms to do likewise.

Just like contemporary multifarious, well publicized leaders in traditionally rooted African Christian churches, Makhanda was gifted with an ability to convince others that he was in touch with God/the Spirit World. Colonial historian George McCall Theal, writing far closer to the time, asserted that Makhanda had been proven unreliable in predictions of spectacular millenarian-type events, but more successful with less dramatic occurrences. Makhanda gained a large following and by 1816 was considered so influential the London Missionary Society weighed up establishing their station at his kraal rather than Gaika’s.

Makhanda’s supernatural claims were instrumental in 1819 regarding drawing ten thousand warriors across the competing chiefdoms to unsuccessfully storm the Grahamstown garrison – a mass attack tactic in the open which the Xhosa seldom employed. Follow-up British victories ensured Makhanda’s capture and imprisonment on Robben Island; to his death by drowning in 1820 during an attempted escape. This literally months before large parties of British settlers arrived to populate the Zuurveld as farmers.

A few years prior to the battle, Lieutenant-Colonel John Graham’s name was given to the military post/future settlement; still commemorated by a sandstone monument on a traffic island in High Street close to the Cathedral. The spot apparently marks where in June 1812, Graham hung his sword on a mimosa tree and selected the Grahamstown site; or so reads the inscription. Initially it was just a military post, a role still retained; during the mid-1960s to early 1990s, generations of white SADF conscripts went through their training at 6 SA Infantry Battalion on the Fort Beaufort road; the base remains active with the battalion; a component of the SANDF’s now overwhelmingly black Infantry Corps.

By 1819, Graham was no longer present at the volatile Eastern Frontier; but long before he even arrived black/white relations at their worst were violent and bitter; the fighting had a long legacy and even lengthier future. One snapshot is the 1793 2nd Frontier War; the ignition thereof derived partly from drought, alongside other simmering tensions; ensuring increased pressure came upon pasture; Ndlambe, then east of the Fish first assisted the colonists in attacking those Zuurveld Xhosa accused of cattle theft; the Gqunukhwebe chiefdom supposedly the most prominent culprits.

This Colonist/Ndlambe alliance was short lived; Boer war losses included 40 dead Khoi servants; 20 farm houses destroyed; and 50-60 000 cattle, 11 000 sheep and 200 horses lost. Swellendam and Graaff-Reinet commandos counter-attacked but could neither subdue Ndlambe’s warriors, nor clear the Zuurveld of Xhosa. Guns and horses could be neutralised by Xhosa fighting bands attacking from concealed positions within the thick bush. The Boer colonists retreated and by 1798 only a third returned to the Zuurveld; a depressingly repetitive pattern that was presented to the British Occupation rulers in 1795-1803 and from 1806.

In 1801-02 another wave of violence broke out, Xhosa and Khoi groupings attacked the Swellendam and Graaff-Reinet districts, destroying 450 farms with stock captures markedly higher than 1793. The authorities were only able to restore a grudging peace because of a collapse in the Khoi/Xhosa alliance over the spoils’ distribution, further hastened by the Xhosa murder of the Khoi leader Boezak.

By1809, Ndlambe had defeated Gaika in battle but was still not paramount over all Zuurveld chiefdoms; Xhosa groupings proliferated even further westwards, as far to present-day Cradock. By 1811, colonists were even abandoning the Graaff-Reinet and Uitenhage districts as roving Xhosa were condemned as “begging” - according to colonist reports - a cover for stealing. The latter will nudge a few school memories amongst of white school history class attendees from decades ago who studied only the condensed Afrikaner-nationalist interpretations of the Eastern Frontier, including the hot coals heaped upon the heads of the missionaries for accepting the Xhosa as human beings made in the image of God, and encouraging British liberalization of laws with the Rule of Law being applied to white, slave and Khoi without fear or favour. Ben Maclennan’s 1986 publication: A Proper Degree of Terror-see below, emphatically refutes the “begging” accusation; insisting that it was Xhosa custom; a hospitality expectation reciprocated to any travelling stranger, black or white – an interpretation only the most naïve would accept within interrogation.

Graham has long had few friends amongst contemporary historians: Giliomee who strongly emphasises the imperativeness of historical context consideration when assessing past controversies, and consistently applying such to the Boers, condemns Graham unequivocally; repeating his attributed remark that the Xhosa were simply “horrid savages"; (Giliomee) stresses the Xhosa had also been labourers and trading partners besides periodic enemies; that Graham was unjust and unrealistic in ordering the pursuit of Xhosa cattle plundering parties to their settlements, where every man would be “destroyed” to inspire within them Cradock’s instructions: namely a “Proper degree of terror and respect”; Cradock viewed the Xhosa as a threat to both British subjects and the colony’s meat supply..

But undeniably it was the fierce colonist criticism - mainly Boer - of the British that spurred Cradock to commission Graham, the new Khoi Cape Regiment commanding officer, to permanently compel all of the Xhosa across the Fish River, first by persuasion and if necessary by armed force. The “Proper Degree” statement was seized upon by generations of historians; not least Maclennan who used it for his damming Graham frontier biography’s title. Thereafter repeated enough to ensure the town's name as irrevocably unacceptable to the ANC and/or any other entity/individual leaning towards Afrocentric historical interpretations. Maclennan sourly concluded his book: “a four-and-a-quarter-million rand monument to the 1820 Settlers looms oppressively from a hill overlooking the city”; perfidiously ignoring the structure’s long stated and acted upon educational/artistic/performing arts role promoting English in Africa in an explicitly non-racial spirit.

The historical context of both Cradock and Graham’s remarks also contain happenings comprehensible within the stresses of a frontier society – an historical pattern neither exclusively South African nor Western colonial. Just as Afrikaners remain aware that Anglo-Boer scars still run deep through certain portions of South African society; the "Long War" phenomenon indisputably applies to the Xhosa; how disruptive and destructive aspects of war still impact upon collective memory. Generations of Africanist, Liberal, Marxist and Afro-centric historians argued markedly strongly that the Frontier Wars traumatised besides materially denuded the Xhosa; that colonist and Imperial actions represented a land dispossession with even genocidal undertones. Such is the power of historical belief and legacy – but also blacking out, denying or even justifying the lot of many frontier colonists who enduring pillaging, violence, dislocation and ruin; such being emphasised by Theal and those who followed him; not least Afrikaner nationalist historians.

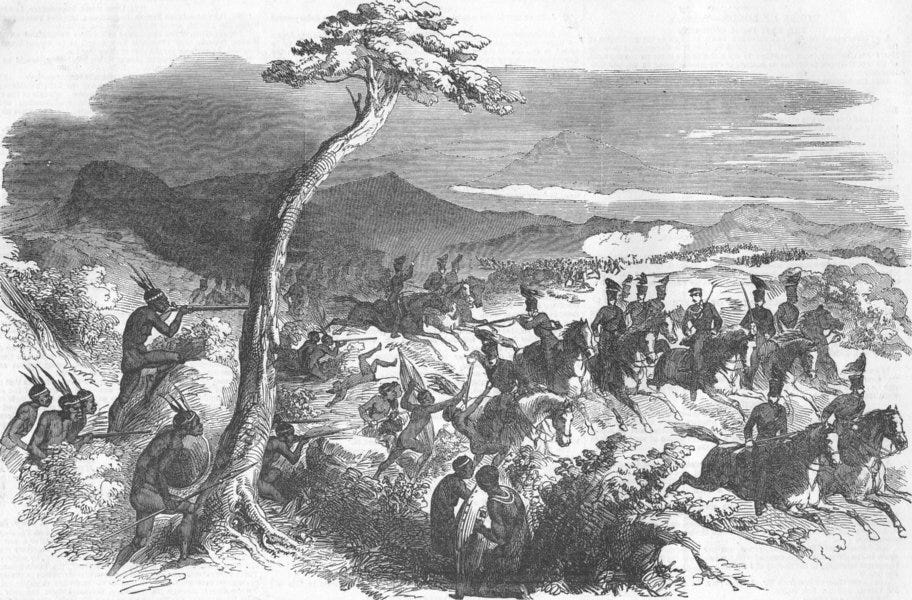

Thus the “Proper degree of terror and respect” opened the Fourth Frontier War and besides his own men, Graham commanded other British troops and burger commandos from the Swellendam, Graaff-Reinet and George districts. With the forces approaching the Zuurveld from different directions, Landdrost Andries Stokenstroom encountered Xhosa of the Imidange and following a parley of attempted persuasion, he was speared to death along with eight Boers and a Khoi interpreter. Graham’s forces continued the wide sweep; fighting was marked by numerous skirmishes; according to the colonists, Xhosa casualties numbered in the hundreds.

The 1811-12 war had mixed results, but Cradock ordered the establishment of fourteen military posts along the Fish River and twelve to the rear with smaller garrisons. Hence some town names of the Eastern Cape; not least Fort Hare, a name iconic in African nationalist development of “Struggle Leaders”. Signal posts were established between the Sunday and Fish River, to observe movement of Xhosa or Boers and communicate such to the posts. Headquarters were located at each end of the line: Cradock west and Grahamstown east. British Dragoons patrolled from post to post accompanied by Khoi soldiers’ expert in the tracing of cattle footmarks. The garrisons’ role included curbing colonists breaching the Fish River boundary in search of stolen cattle; Khoi groupings also had cattle stolen and looked upon the British military for assistance and restitution.

From June 1817 for pecuniary reasons this garrison was drastically reduced; the resultant weakening allowed an increase in stock theft with Ndlambe’s followers in the forefront and military casualties occurring during recovery. Colonists complained that cattle theft was increasingly rife with branded stock driven far to the east and exchanged for non-marked cattle. Makanda via messengers had supposedly appealed to all western Xhosa, promising victory and threatening the wrath of the spirits against those who held back from attacking both Gaika’s people and the colonists. Some intra-Xhosa paramountcy disputes were temporarily eased; Gaika appealing for and received British and burger support; but not enough to prevent his near-annihilation by Ndlambe.

The Grahamstown attack followed at sunrise on 22 April; the Xhosa numbering 9000 to 10 000 men, launched a three-column assault against the small cluster of houses and the barracks some distance away. The troops held their positions; the Xhosa retreated, rallied, and attacked again; about 500 Xhosa bodies were counted; British casualties were three dead and five wounded. (not unlike Blood River in 1838). This all frontal attack by the Xhosa was unusual, for their fighting style had always been to operate in much smaller marauding bands, concealed and ambushing, using the dense Eastern Cape river valley bush.

From the colony’s perspective, defeat at Grahamstown could have meant the Xhosa sweeping far further afield than had occurred in the past; possibly to the Gamtoos River and beyond; the vital supplies of muskets and ammunition in Grahamstown would have been seized – certainly the Boers of the Eastern Cape would have suffered further losses. Makanda’s fate hereafter was sealed; British reinforcements including additional Khoi troops arrived followed by burger commandos. As Theal puts it: They scoured the jungles along the Fish River, drove the hostile clans (chiefdoms) eastward with heavy loss, and followed them to the banks of the Kei; Ndlambe’s power was broken.

Makanda’s legacy lived on; Xhosa so influenced refused to acknowledge his death, believing him immortal; Only in 1873 were his carefully preserved mats and ornaments finally buried. But later disillusionment over Makanda’s legend produced a Xhosa proverb – Kukuza kuka Nxeke – the coming of Nxele – you are looking for someone you will never see.

The past bears down heavily upon the present: Makhanda’s defeat, Robben Island incarceration and drowning death; his 2019 resurrection; juxtaposed against Mandela’s more than a century and a half imprisonment and liberation, with his triumph of magnanimity which draws the blessings of even the most conservative whites.” For Xhosa, the renaming of Grahamstown might be succour to the humiliations of historic black military defeat; the loss of communal land. Or is it just the contrived ANC political triumphalism of an historically failed mystic? Or is it a bitter sop to the reality of the all-powerful English language, the foundations of Grahamstown’s university and elite schools, its historic churches and much more, rooted in the culture of the British Settlers and their descendants – not to mention the roadside name boards identifying ownership of the numerous prosperous farms in the region once known as the Albany – the Zuurveld.

For many whites no doubt, the Eastern Frontier history prompts a fearful and angry resonance of farm attacks and urban crime; for some even, perhaps coupled to the loss of a familiar place name associated with school and university nostalgia; the disappearance of an identity point within a heritage seldom reflected upon by most of them, despite its ubiquitous and rather obvious resilience or even sustained cultural triumph. The latter view appears to remain all vivid and still deeply felt in black political groupings and with demographics overwhelming on the latter’s side, is it this which imposed the name change? Time will tell if whether within everyday discussions, references and popular culture, the name Makhanda will ever completely take root over Grahamstown – two names and histories representing so much, some intertwined, but also so inextricably different.

Dr Rodney Warwick completed a BA (Hons) in Historical Studies at UCT during 1985-88; and later an MA with distinction then a PhD, also through UCT; he writes press articles on SA historical topics, particularly military, social and political history; published several journal articles and is currently engaged with writing/research on Anglo-South African historical identity and Cape Colonial History; particularly the Eastern Frontier.