Delville Wood and the Great War

Written by: Hügo Krüger

Napoleon Bonaparte once said that history is nothing more than the fable which we have all agreed upon. He referred to the tendency of every ethnic group or culture to put themselves at the center of history and then to whitewash the bits and pieces that they do not like. This confirmation bias is best shown in the South African history curricula. School history syllabus are always touching on the edge of propaganda.

The National Party never mentioned the Soweto Riots or the Horrible death that Steve Biko suffered from his head injuries; the British government tried to brush over the atrocities of colonialism and the Anglo-Boer war; and the African National Congress does not want us to learn about its brutal people’s war or or the lie of Cuito Cuanavale. Yet the truth always lies below the surface. And truth is often the enemy of power.

Cultural identify and often just personal pride have always come in the way when the myths of our own society gets questioned. The intellectuals of the day have always tried to make their side seem holier than thou. South Africans do not know each other’s history and until we face this bitter truth, all our high school curricula will stay susceptible to state indoctrination. We will be presented with the history that we like. History will be used to divide us, and we will be lied to.

A society that constantly tries to deceive itself is not one that is destined for a stable political future. As Francis Bacon would say, knowledge is power and, in this case, an objective knowledge of history grants one the power to not be influenced by the government of the day’s doctrine.

When a philosopher, a nationalist, or a theologian gets hold of the gaps of our historical knowledge then it leaves us vulnerable to the doctrines of their ideology. Nowhere is this point better shown to me than the complexity surrounding the battle of Delville Wood and the events before and after the First World War.

The Battle of Delville Wood is the largely ignored story of a young South Africa. The country was barely a decade old when it decided to join the side of Imperial Britain in the First World War. The memorial site in France deserves to be treated on the same level as the Voortrekker monument, the Woman’s Monument and the Apartheid museum and yet its centenary went largely uncelebrated back home.

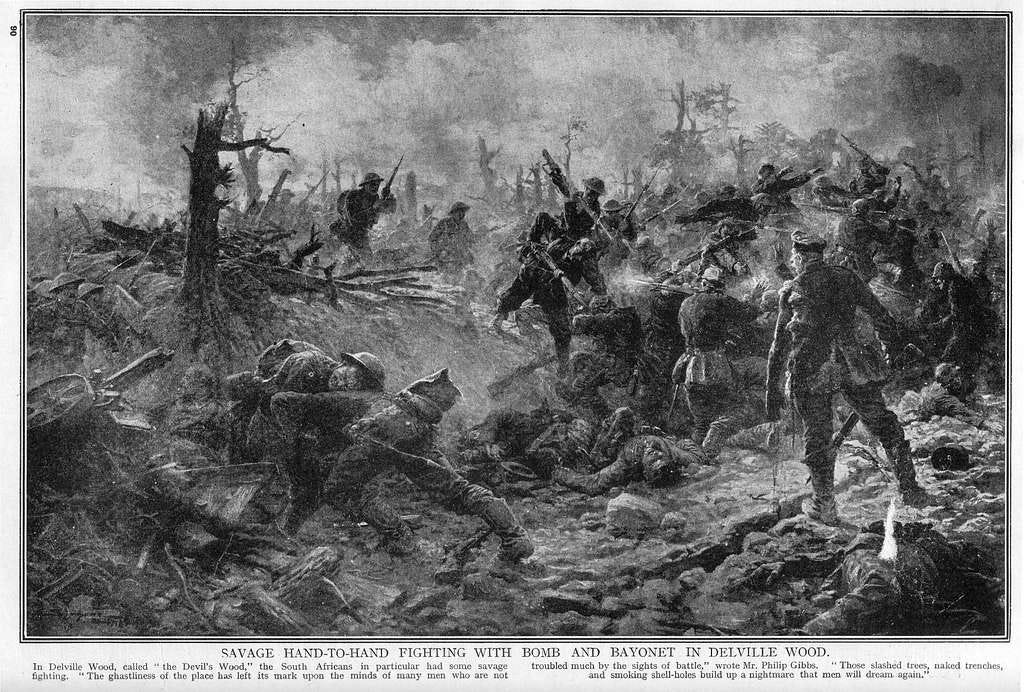

Delville Wood is not far from the small-town Albert. The memorial is dedicated to the battle of Delville Wood that took place, as part of the battle of the Somme, during the First World War. There is also a section that commemorates South Africa’s entire participation in WW1. At Delville Wood, the 1st South African infantry brigade made their debut on the Western Front as part of the allies’ larger the Somme offensive. The battle itself took place between the 14th of July and the 3rd of September of 1916. Of the original 3433 soldiers that entered the Bush, only 750 remained. The loss on the German side was just as horrible.

Thousands of young black and white men were pulled into the war of which they had little to no fight in. South Africans fought in many of the theaters of the war. In South West Africa, in East Africa, in Palestine, on the sea and in the European Theater.

The First World War was the first time that the Afrikaners and English fought together under one title: South Africans. South Africa was a young country that was barely a decade old. The memories of the scourge earth policy and the concentration camps still had a bitter zeitgeist in the air. The government of the time, under the leadership of General Louis Botha, decided (with popular opposition) to join the war on the side of the British Empire. It might help to reflect on what this decision meant for South Africa and the century that would follow and perhaps also on the larger decision of Great Britain to enter WW1. What were its implications for the United Kingdom, the British Empire, Europe and the World?

Governments always recruit young men, because they are still unwise. They sell them the old lie Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori est, as Wilfred Owen put it. Governments put their cause as noble and just, but it is difficult to justify a just war when some of the boys who died in the trenches of France were as young as 14. A child of that age certainly wasn’t ready to kill. Many of the soldiers joined the war, not out of conviction, but because they were from poor backgrounds and had no other means of income.

The whole political class, church leaders and University councillors justified the war as one for civilisation. Or as in Woodrow Wilson’s words: “the war to end wars”.

As always those who advocate for war are never prepared to suffer the ramifications of their own ideology. During the Christmas Truce of 1914, it became apparent to the allied soldiers that they had more in common with their Christian German opponents than the political leaders that led them and yet the war raged on for another 4 years. Another theme to investigate is that Great Britain did not introduce conscription until 1916 and therefore the men that died first were the best that their country had to offer.

The British Author Peter Hitchens once wrote that it would be an understatement to say that the First World War was the biggest calamity in Western history since the fall of the Roman Empire. It affected every corner of the world as there has been few comparable events that has changed the map of the world on such a scale as the treaty of Versailles. This was the war that set the stage of the political events that would lead up to the 2nd World War and the disasters that would follow. It also set the stage for the events that followed in South Africa for the century that was to come.

General Louis Botha’s decision to enter the war by attacking German South West Africa hurt his own legacy among Afrikaners. The Germans, after all, supplied the Afrikaners with Mausers during the Anglo Boer war and many Afrikaners were also of German descent.

During the war, the Maritz Rebellion broke out. The Rebellion was an emotional event, whose memory the National Party would exploit for years to come. A young man, named Joppie Fourie, was hanged. Joppie Fourie was anything but an innocent rebellion leader, but he dared to ask an uncomfortable question:

“Why should South Africans be fighting for England after the events of the Anglo-Boer War?”

His punishment was death be firing squad and it would not be the first or last time that the government of the day would label dissidents as terrorists. As late as in the 90s, we were still singing a song that praised Joppie Fourie in Afrikaans schools.

General Louis Botha was a complex man who tied to reconcile two conflicting South African groups: the English and the Afrikaner. Had it not been for this support of WW1, then his legacy among Afrikaners might have been greater. He had the foresight to negotiate with Great Britain at the Treaty of Vereeniging, but not the savvy to keep us out of WW1 at the warning of General Koos de la Rey. The complexity of the country’s first prime minister becomes even more difficult to understand when one learns that he lost most of his children during the Anglo Boer War.

One forgets that little over 100 years ago war was, as Thomas Hobbes pointed out, the natural state of humankind. The memorial of Delville Wood depicts this tragic event as it was, but it is just one of the thousands of grave sites that commemorate the Battle of the Somme.

The oak trees surrounding the site symbolises the complex link between South Africa and Europe. The trees were planted from seeds of oak trees that were initially brought to South Africa by French Huguenots. The protestant Huguenots were expelled from Catholic France when the Edict of Nantes was revoked. It is the story of the ancestors of many white South Africans who came to Africa, because Europe for most of its history was involved with brutal conflict. To paraphrase the Eagle’s song, the Last Resort: they packed their hopes and dreams like a refugee. They were looking for a place to stay or a place to hide.

The Delville wood memorial also tries to bring out the history of the many black South Africans that fought under the banner of South Africa – in a time when they had little to no rights back home. One of the black South Africans that died in WW1 was the grandfather of Tito Mboweni. His grandfather died when the SS Mendi battleship sunk. I doubt that we will ever know the true experiences of many black South Africans during the war. Historians did not care to record them.

One can also wonder if the leaders on the eve of the breakout of the war would have reconsidered their position had they known its consequences. Would they have given diplomacy a chance? Could Apartheid have been avoided had the fears of communism not broken lose? Or would colonialism had survived for decades to come? Wars are easy to start, but they certainly do not only end with a peace treaty.

At the end of the war, Great Britain was in decline. The eastern rising would eventually pave the way for independence of the Irish republic. In the decades to come, South Africa, Canada and Australia would become dominions and a growing number of African people would become politically conscience. It would lead to Gandhi’s non-violent protest, and in a few decades the beginning of the Winds of Change in Africa.

The French republic was also damaged to the point that its overseas colonies began to ask the same questions that they themselves asked during their revolution. Many soldiers from Africa and Asia fought for France, but they were living under Apartheid like systems back home. They appealed to the human Angels of France’s revolution:

“What does liberty, equality and Fraternity really mean?”

The war would also destroy the Ottoman and Habsburg empires with the creation of unstable states such as Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. It would not create a stable Balkans of Central Europe. The badly drawn borders left a sensitive scar open when a madman called Adolf Hitler in a few years to come asked for the Sudetenland. Neville Chamberlain appeased him.

The political consequences of the Sykes–Picot Agreement that carved up the middle east into badly defined nation states are with us to this day. The unanswered question as to who controls the holy land is as vague today as it was after the Balfour Declaration. The Kurds are still left with no homeland of their own. They were left vulnerable when Sadam Hussein invaded Iran and started with his genocide.

With Russia’s exit from the war, the Soviet Union was under communism, a brutal experiment that would eventually cost more lives when fanatics tried to think themselves wise enough to change human nature under their own ideology. The Tsar was a brutal tyrant, but in his entire lifetime he killed as many as Stalin killed in one day.

With hyperinflation throughout the Weimar Republic, Germany, Italy and later Spain would fall to fascism. The humiliation brought by the treaty of Versailles would set the stage for WW2 and the holocaust.

America become a world power and reconsidered its worldwide isolationism. Before the war, the USA had an army the size of Bulgaria’s, afterwards it would be left with what General Eisenhower termed the military industrial complex.

Even countries that were largely unaffected by conflict, such as Argentine, with its economy highly dependent on exports to Great Britain would descend into a century of decline and, later after WW2, fall under the dictatorship of Juan Peron.

Back home in South Africa, Afrikaner Nationalism began to take its firmer grip on the white South African psyche. Shortly after WW1, the great depression would take place and then another world war would condemn the generation that followed to more conflict and great atrocities. At the end of the 2nd World War, South Africa’s slide towards Apartheid would be in full force and it would eventually lead to further erosion of native rights. Decisions that were only reversed at the near end of the previous century.

South Africa’s participation in WW1 highlights harsh realities of our complex past. It brings out the interdependence that black and white South Africans had since the country’s beginning of the Union. It points out that the master and servant relationship that is often ascribed only to Apartheid predates 1948. The battle of Delville Wood showed that Afrikaners and English – despite their deep divided convictions could on the day fight together as South Africans. Perhaps this is the only lesson to learn from the war. During the conflict of battle, soldiers forget about their origins and some of the remarkable stories of courage and cooperation are brought to light.

History is always full of nuance and difficulties, because human nature is complex. Historical figures such as Generals Louis Botha or General Jan Smuts miscalculated their decisions and brought forth the strong nationalism that was used by the Afrikaner Broederbond to sell anti-Englishness and Apartheid to their voters for decades to come. They underestimated the largely fringe purified Nationalist party of D.F. Malan. In hindsight, this was foolish, but no one on the eve of the battle predicated the outcomes that would be the outcome.

On a more global stage, South Africa was and still is to this day a much smaller player in larger geopolitical conflicts. Our entrance to the war shows our dependence on foreign powers. We are not isolated in a global community. The tale of history always reads as a narrative. As Mark Twain said, it never really repeats itself, but it does rhyme.

The conditions that created the first world war were unique to the particularities of its time, but one needs to ask the question if the leaders at the time of war knew about the consequences of the Napoleonic wars, the Mongol invasions, or the Brutality of the 30 years’ war. Perhaps then, they might have had a different reaction when they heard that Franz Ferdinand was murdered by Serbian terrorists. Perhaps the brutality of the war could have been avoided had they knew that human beings were capable of genocide. The exact same genocide and ethnic cleansing that they practiced in South West Africa, the Belgium Congo or under the Scorched Earth policy of Lord Kitchener.

South Africans today have the insight of all that they had in the mistakes the people in the beginning of the last century made. We know that the recipe of might is right leads to further conflict and disaster down the road. It appeals to the darker angels of our nature.

History and knowledge of war equips us with more insights into our own nature and experiences when we are challenged to defend our visions for society. It allows us to see the predictable consequences or our own thoughts and actions, especially when so many ideologies that people today defend with vigour have already been tried and tested before – mostly with disastrous consequences.

Lest we forget Delville wood and the legacy of the South Africans that participated in the great war. Lest we forget the lessons that it left us.

To quote the words from the memorial:

“Their ideal is our legacy, Their Sacrifice our Inspiration”

Hügo Krüger is a civil and nuclear engineer. He served on the SRC at the University of Pretoria in 2011 and had the portfolio Multilingualism and Culture.